Continuity Should Be a Toolbox, Not a Straightjacket

- styrofoamturkey

- Dec 30, 2021

- 14 min read

Updated: Mar 13, 2024

Way back in my first post, I mentioned that I tend to like long stories. It’s not a coincidence that my favorite television series is Doctor Who, a show that is coming up on 6 decades and 900 episodes worth of stories as I write this. I like stories with longevity to them.

It fascinates me to see characters grow and develop over long durations. One of the many reasons Spider-Man is my favorite comic character is the fact that we effectively get to follow his life from adolescence through young adulthood, into marriage and beyond. This is paralleled with watching him grow as a superhero as well. If reading Spider-Man comics from today, in 2021, felt just like reading Spider-Man comics from 1963, something wouldn’t be right.

Longer stories present a larger, overarching, meta-narrative. They present us with a big story built out of lots of smaller stories. Sometimes this larger story is planned. More often it’s just an organic outgrowth of stacking up the smaller narratives in sequence. In either case, it can be fascinating to explore and contemplate the way the characters and situations change over time.

And every once in a while, they change something big.

Sometimes it’s a change that goes forward like when a prominent character dies or otherwise leaves the narrative. Sometimes it’s a change that goes backward like when backstory that we’d previously been unaware of is filled in. And sometimes they flat out change something we thought we already knew.

For some people, that last one really doesn’t go over well.

In general, going back and changing a part of a story we thought we already knew is called “retroactive continuity” or, more generally, a “retcon.” Sometimes retcons are relatively simple. For instance, in Captain America Comics # 1 the villain known as the Red Skull accidentally rolls over on a hypodermic needle full of poison and dies. Later, in Captain America Comics # 3 (after the creators had received enough letters to realize the Red Skull had been the most popular villain in # 1) we see a new scene in which the Red Skull gets up a few minutes later apparently having been able to survive the poison. Thus, the Red Skull’s death has been “retconned” out of existence. Many years later, in Tales of Suspense # 66, we would learn that the character in those two issues wasn’t even the “real” Red Skull, but rather an imposter. This is also a retcon.

Arguably, the two I mention above, the Red Skull’s resurrection and the revelation that the character isn’t actually the Red Skull, are two different kinds of retcons.

The first simply adds a scene we hadn’t seen before, continuing on with the previous narrative information still being entirely correct. Everything that happened regarding the Red Skull in Captain America Comics # 1 still happens, it’s just that his story doesn’t end there but rather continues in Captain America Comics # 3.

The second retcon is slightly different in that, while it doesn’t change the events of any of the previous narratives, the mere idea that the character we’ve been identifying as the Red Skull is not the genuine article changes the whole tone of those early appearances to be something different. It doesn’t change the narrative, but it heavily changes the implications of it.

Sometimes, retcons go even further than that. To continue with my Captain America theme, the Red Skull story (and a few others) from Captain America Comics # 1 later get “redone” in some issues of Tales of Suspense. The same events are depicted, but with changes in detail and artistic choice. (Including the fake Red Skull not getting poisoned at the end of the story this time.) So, given that they are both presented as part of the Captain America narrative, which “happened?” It pretty much can’t be both, as it beggars belief that Captain America experienced virtually the exact same events twice in a row. So which takes precedence? The original story or the recreation? Opinions on this abound.

And what about things that take things even further than that? Sometimes an ongoing story presents us with things aren’t simply incompatible recreations of previous stories, but rather the narrative expressly goes out of its way to tell us that the previous narrative was wrong or didn’t actually occur.

Since Captain America seems to be my go-to for retcon examples, I will use it for this type as well. Captain America’s origin story is presented in Captain America Comics # 1. A more expanded version of Captain America’s origin appears in Tales of Suspense # 63. In itself, this is more like the first kind of retcon. It’s the same story with a bit of expansion (although there are probably shades of the third type too, with little details being changed.) Then, many years later, in Captain America # 225, we see an origin for Captain America that is significantly different from the one we’ve seen before. Enough so, that it effectively means the previous origin story must not have actually occurred. (And, to make things even more complicated, in Captain America # 247, this new origin would be revealed, itself, to be false, restoring the original.)

If you're trying to look at the ongoing narrative of Captain America, this can start to make things a bit confusing. It becomes tough to know what is and isn't (fictionally) true at any one time, with the added burden of knowing that, at any point, what you've believed to be true might change.

It's worth noting that sometimes these retcons aren't even deliberate. Particularly with very long running stories, there tend to be enough creators and plotlines that it's almost inevitable that someone will make a retroactive change at least accidentally, if not deliberately, even if it's something like giving a character a middle initial that's different than one they already had. (Stand up James T. Kirk. Or should that be James R. Kirk?)

The longer a story lasts, the more likely this is to happen. It's not even limited to stories with multiple creative voices. Even single creators will occasionally change things, either accidentally or because they look back and realize they'd rather things be a little bit different. To take an older example, there are express contradictions in the backstory of the Sherlock Holmes stories that are written by Holmes' original creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Because of this, some people...well, really hate retcons. For some, the idea of what they already believe the story to be is sacrosanct and retroactive changes, ones that make you view what you'd previously presumed to be true differently are an affront to that. Their sense of the believability (or at least verisimilitude) is shattered when a retcon happens.

Despite my love of long narratives, I don't actually share that view.

I see retcons pretty much like any other story element. They can be good. They can be bad. They can be a little bit of both. To hop back on the Captain America train, I remember thinking, for years, that the one death I hoped would remain permanent in comics was that of Cap's WWII era sidekick, Bucky. Bucky's death had been a moment that affected Captain America's character for decades and tampering with that seemed like dangerous ground.

Then they brought Bucky back. And it was...kind of awesome, really.

As I read the new stories with Bucky in them, I realized that I had been thinking of the idea of Bucky's resurrection in terms of story regression...that it reversed the progress the story had made since (and arguably because of) the character's death. But, in reality, far from reversing things, it actually opened up new doors, presenting new avenues for the story and characters to explore. It expanded the possibilities for storytelling in the Captain America narrative...and then made good use of those opportunities.

When a story goes on as long as Captain America (which started roughly in 1941, so it's been going for about 80 years now) you need new opportunities. You need to explore new paths and avenues or storytelling, otherwise you're just going to end up recycling the same stories over and over. Even if you choose to tell similar stories, you need to put new twists and spins on them.

And, with all due respect to people who hate them, a retcon is a perfectly valid way to do that. That doesn't mean every retcon is good. (13 years on and I still think erasing Spider-Man's marriage was a terrible idea.) But it means that when a retcon is bad it isn't bad just because it changed something.

Stories are supposed to change. Stories are supposed to evolve. That change and evolution is not automatically limited to that narrative’s future. Consider the bombshell of Luke’s parentage in The Empire Strikes Back. It’s one of the lynchpins of the entire Star Wars story. It’s also a retcon. The previous film had not been ambiguous about the fate of Luke’s father. Darth Vader had betrayed and murdered him. The idea that Darth Vader was Luke’s father is a change to the narrative, not just an addition. And yet it’s what everybody now knows and accepts to be the story of Star Wars. (Apologies if I spoiled a plot point for a 41 year old movie for anyone.)

No, the mere fact that something gets retroactively changed isn’t automatically bad. Now, I occasionally hear people say something along the lines of “That means that you should only make a retroactive change if it’s going to serve a good purpose.” This is a bit of a loaded statement. First, it presumes that “a good purpose” is something universally agreed upon, as if it’s not possible for the creators of a work to think they’re doing something for a good purpose but some others who experience the work to disagree. (And, of course, for different people who experience the work not to agree on whether or not it served a good purpose. I have met people who think dissolving Spider-Man’s marriage was absolutely necessary for the future of the narrative.)

The “only for a good purpose” complaint also usually comes as part of a complaint about a retcon that someone didn’t particularly like, which means that they’re speaking from a position of hindsight and expecting creators to accurately predict, ahead of time, which storylines will and won’t go down well with everyone else. That is not a reasonable expectation Some might say that they should err on the side of caution in those circumstances but I think that just leads to timidity and endless “safe” storylines. “Safe” shouldn’t be mistaken for “better.”

More than that, the “only for a good purpose” complaint still needlessly separates the concept of the retcon from other story concepts, placing extra hurdles on retcons that they need to leap over that other story elements don’t have to deal with. Other types of story innovations can be tried at will, but retcons must be vetted extensively ahead of time, lest the precious continuity of the past be touched.

Because that’s really what it all comes down to: How we view continuity. How we see the ongoing story. Some people view it as unassailable, untouchable, as virtual Holy Writ. I have even seen some people vehemently put forth the idea that the current creator of a story is there for the express purpose of honoring what has come before. Because of this, the very idea of presenting a story that even vaguely implies that the previous lore of the narrative might not be 100% accurate is verboten. The current creator is there to venerate the works of the previous creator(s), to curate them like exhibits in a museum, pristine and untouched.

Well, I’m sorry, but that's not what a creator’s job is. They aren’t there to preserve the story. They’re there to create more story. In any direction that they feel makes for an interesting one. If that means some of the previous continuity needs to be lightly pruned, so be it. If it means it needs to be cut with a scythe, so be it.

Because continuity is not Holy Writ.

Continuity can be fascinating and interesting and it only takes a cursory look at the way I examine things to know that I find it to be both of those things. But when it starts getting treated like a boundary, like it’s previous limits can’t be pushed or widened, then it is no longer a rich source of enjoyment. It’s just a straightjacket.

Lest we forget (and it’s easier to do so than people think), fiction is not the explication of real life events. There is no “real” version of events that must be depicted, and thus no “truth” to deviate from. Whether I like it or not, Spider-Man wasn’t “really” married and changing that within the narrative isn’t some sort of fundamental misrepresentation of “fact.”

What is continuity then? It's a toolbox. It's a big, wonderful, container of tools that you can pull from to make your story interesting. You take them out, as needed, to craft your story in the present, to make it as interesting as possible as a story in and of itself, not just as an homage to the past.

Because that is the actual job of a creator, to fashion the stories in the now. They're not there to preserve the past like some fly in amber. No, they're here to build the present. The future? That gets left to the creators of tomorrow. Maybe the works of the current creator will be frequently pulled from the toolbox. Maybe they’ll get left there forever. Maybe they’ll get replaced. But those maybes aren’t what the current creator is invested in. The current creator is making the now.

For an example of how retcons can make things more interesting via having an expansive view of continuity rather than a constricting one, I circle around, once more, to Captain America.

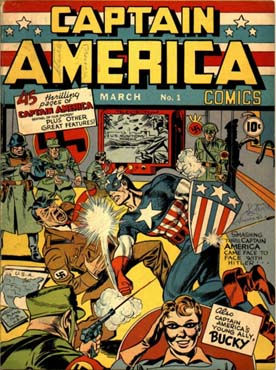

Captain America was a product of World War II, essentially an entertaining piece of pro-U.S. propaganda, particularly in regards to portraying the country as opposed to the Nazi Party. The cover of Captain America Comics # 1 quite boldly portrays Cap punching Hitler on its cover.

Captain America Comics lasted from roughly 1941-1949, at which point superhero comics briefly went out of fashion for a while.

There was no actual end to the Captain America narrative at that point, the book simply shifted briefly to more horror-themed tales, then quietly ended. Comics moved on to other genres.

In 1954, an attempt was made to revive Captain America. It started with him making an appearance in a preexisting book called Young Men # 24. Then Cap’s own book picked up again up with the same numbering they’d left off at in 1949. The series reimagined Cap as fighting communism. (Not really surprising. It was the ‘50s.)

Cap’s revival was part of a larger attempt by the company to reignite interest in their ‘40s era superheroes and that attempt didn’t work very well. Despite being pretty unequivocally the most popular of the ‘40s Marvel heroes, both then and now, Cap’s revived book lasted only three issues and then he returned to non-publication.

In the late ‘50s, however, there was a resurgence of interest in superhero comics (one that has arguably lasted up through the present.) In 1961, Marvel got back on the superhero bandwagon with Fantastic Four # 1 and over the next few years grew a pantheon of characters who still exist to this day.

And, in 1964, they brought back Captain America.

That they brought him back wasn’t a retcon. But how they brought him back was. In Avengers # 4, Cap was found, frozen in ice, held in suspended animation. In that issue, he recounted the tale of how he had become frozen (which included the death of Bucky) toward the end of World War II.

Which meant that none of Cap’s “commie smasher” adventures could have happened. Indeed, his later adventures in the end of the ‘40s couldn’t even have happened if he’d been frozen before the war ended. Those stories had effectively been erased.

Now, a fair amount of people weren't particularly upset by that. To borrow the parlance I mentioned above, many would feel that those stories had been erased for "a good purpose" because a lot of people didn’t think they were particularly good. (Myself, I think the '50s Cap stories have a sort of kitschy appeal but they're no masterpieces.) Still, I imagine there were probably people who liked those stories and were bothered by their ejection from the continuity. Nevertheless, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby had used the tools from the toolbox that allowed them to tell the story that needed to be told in 1964, not 1954.

But that wasn't the end of things. A while later, in 1972, they began a storyline with what initially appeared to be a duo impersonating Captain America and Bucky, brutally attacking poor people, particularly people of color. What is eventually revealed is that these characters were, in fact, the ‘50s Cap and Bucky. No longer ejected wholly from the continuity, these two were retconned as separate characters, who had adopted those identities in the ‘50s but whose sanity had slipped considerably over time, now coming to view anyone who didn’t fit their antiquated view of American ideals as “commies” who needed to be stopped with maximum force.

More than simply a change in backstory, this afforded the narrative the chance to examine the concept of Captain America, particularly how Cap’s patriotism could be co-opted into jingoism and bigotry if taken to extremes. It wasn’t simply an external examination either. The original Captain America was forced to confront that notion within the story itself, in a conflict of ideology and physicality, the latter also serving as a metaphor for the former.

The retcons didn’t stop there, either. In 1977, a writer named Roy Thomas, an aficionado of the ‘40s Golden Age of Comics, gave us backstory devoted to explaining away the adventures of Cap depicted between when he was frozen and his ‘50s appearances. To this end, two other heroes, the Spirit of ’76 (one of Thomas’ own creations) and the Patriot (a Golden Age contemporary of Cap) were determined to have successively taken on the Captain America identity in order to keep the patriotic symbolism he represented alive after the disappearance of the original.

Not mere continuity box-ticking, however, Thomas wove a tail of two men both of whom had been inspired by the original Captain America and their attempts to live up to his legacy. Indeed, that inspiration becomes almost generational, as the whole reason the Patriot takes up the Cap mantle is to honor the Spirit of ’76 when he falls, sacrificing himself to save lives.

From these retcons, the seed is also planted for the idea that Captain America is a legacy character, more of a symbol than a single individual. Now, an argument can be made that his symbolic status was pretty obvious from the beginning (he does wear a flag for a costume, after all) but establishing this succession of characters who have inhabited the role changes it from generic symbolism, that anyone who puts on the suit stands for the same thing, to a more nuanced version where different Caps symbolize slightly different takes, not all of them as pristine as that of the original. It allows Captain America to represent different viewpoints on America.

Establishing Cap as a legacy character in the past also provides another tool for the toolbox of future creators, paving the way for both the idea that the original Cap might become disenchanted with his symbolic status (as he did when he briefly took on the separate identities of Nomad in the mid-‘70s and the Captain in the mid-‘80s) and that others might take on the identity in the future (like John Walker in a fascinating examination of more gung-ho ‘80s patriotism, Bucky in the 2000’s which gave us a version of Cap that was forced to confront the symbolic blood on the hands of the country, and the Falcon which allows for a version of Cap that sees things from the perspective of the less enfranchised members of American society.)

A few years ago, there was even a storyline which retconned the whole of Cap’s backstory, rewriting him as having been a secret villain for pretty much the entirety of his existence. Importantly, however, Cap didn’t think of himself as the villain. Rather he was a fascist who thought he was in the right. In today’s day and age, with a fair amount of real people espousing what amounts to fascist ideology while also claiming to be in the right, that seems like the perfect story for the now. Certainly, at the end of that story, when the original, more noble version of Cap is recreated and wrests control from the fascist one, it presents a level of satisfaction that couldn’t be matched just by not having tried the fascist-Cap storyline in the first place, even though that would have left Cap’s continuity untouched.

All that because someone decided to change something big. All that, impossible without changing something big.

Which is why continuity needs to be a toolbox, not a straightjacket.

Previous Post: The Fantastic Four

Previous Musing: Fear and Wonder

Next Post: The Cave of Skulls

Next Musing: Elasticity of Continuity

First Post: Stories

Weirdly, as I've wound up rebooting/reviving the pokemon parody nonsense I was writing 20 years ago because brains are an asshole and whatever I might like to be writing instead I haven't actually been writing that for the 17 years or so I haven't been actively writing this pokemon parody but since it would now like to cooperate with me and write something I may as well let it write what it wants to write, I've come to realize - and recognize that this was the case 20 years ago as well - something about me and my relationship with continuity.

For all I profess that continuity matters for the length of the story and not a line longer, because…