"High" and "Low" Art

- styrofoamturkey

- Sep 11, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Feb 4

Stories are an art form.

I believe that firmly and totally. I believe that the words of a fictional work are akin to the oils of a painting or the notes of a song. Stories as art are not limited to prose, either. Film, television, even comic books are art. Indeed, stories are by far my favorite form of art. That's why so much of my time is devoted to studying them.

They're not the only form of art I like, mind you. I appreciate painting and drawing (hence my love of comics.) I admire the art of cinematography even divorced from the story it is being used to tell. Like most people on the planet, I enjoy music. I am fascinated by dance and choreography. When I was younger, I was quite obsessed with martial arts movies and as I got older it dawned on me that what I saw in those was much more like an intricately choreographed dance than actual fighting.

And I like a good joke. That's right. I think jokes are an art form as well.

I like all of those forms of art to one degree or another, despite my personal talent for most of them being pretty limited.

I also like them despite whether they're regarded as "high" or "low" art. I like Shakespeare and Doctor Who. I like The Godfather and I like Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure. I like the Mona Lisa and I like comic books. More importantly, I don't like these things differently based on that "high/low" art divide and it occurred to me that it might be worth examining that divide itself and whether it stands up to scrutiny.

The Divide Between "High" Art and "Low" Art

What is the actual divide between "high" and "low" art? And is it a valid one?

If my opening didn't do so already, I'm going to tip my hand early on this one and say my answer to that second question is no. In order to get to why that's the case, I need to look at the first question, though.

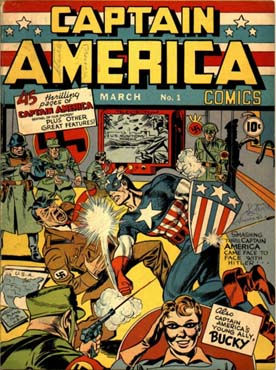

One of the first things I note about the divide is that it's changed over time. There are many art forms that, today, are considered respectable "high" art that were once looked upon as "low" art. Shakespeare's plays are generally considered to be amongst the most brilliant artistic achievements for the stage but in his own time Shakespeare's plays were considered lowbrow populist works. The whole media of film was regarded as little more than a crowd-pleasing curiosity in its early days, a poor cousin to theater. Television has, for decades, been regarded as film's less-impressive cousin, although these days it's making impressive strides toward respectability as a true art form. Novels used to come out in serial form for cheap public consumption, writers literally being payed by the word. Comics are generally still regarded as a "low" art (albeit a more socially acceptable one than in the past) but it's worth noting that some individual comic works, like Watchmen or Maus, do get acknowledged as good enough to stand amongst their prose peers. (Animation, sadly, still tends to be regarded as "low" art in the western world but I have hope for the future.)

Further, most of these changes have happened organically over time. It's not like Shakespeare's plays "got better" in the intervening centuries between their populist roots and their current status as "high" art brilliance. There's no official body that declares when a piece of art "rises" from humble "low" art to dizzying "high" art. One of the reasons it's hard to treat this divide as particularly important is that time clearly makes it permeable.

Then there's the question of what the dividing line between "high" and "low" art actually is? As mentioned, there's no governing body who decides such things. It just sort of...happens. If my grandfather saw me reading a book, he approved. If he saw me reading a comic book (or a "funny book" as he called them) he thought I was wasting my time. Whether the individual book or comic was well made or not did not come into it. And this was a man who watched daytime soap operas religiously. But that was just my grandfather. He was an example, not an authority. And I loved him.

Where, then, does the separation lay? What makes art "high" or "low?" Well, there are a few possibilities.

One factor I see posited a lot is the matter of what motivates the art in the first place, whether the goals are commercial or artistic. Is the artist driven by the desire for money or love of the art itself?

I think this is a bit of a false dichotomy, myself. The desire to make a living and love of the art one works at are not incompatible. If one looks back at the artists of the past one finds that many of them were bound into a system of patronage in which they created their art for specific individuals, patrons, who payed them for their work. This includes some of the greats like Da Vinci, Wagner, Beethoven and Mozart. I don't think anyone is going to seriously question the talent or love of their art those men possessed. But they also worked for money.

Because people need money to, y'know, live.

Money is not optional part of life. Very few of us are lucky enough to be born rich or to luck into wealth during our lifetime. And if one pursues vast wealth as an occupation, art is hardly the most lucrative profession to go into. Artists who strike it rich are exceedingly rare. The "starving artist" stereotype didn't come out of nowhere.

So, if the goal were really money and not love of the art, then...well, most artists would've chosen a different career. Being an artist, of any kind, is an exceedingly hard way to make a living. That's why many artists pursue their passion on the side while they work in other fields in order to support themselves and their families. But, of course, the less time one has to spend on one's art, the less it develops.

Recently, I've noticed, we have had the beginnings of a return to the patronage system with things like Patreon and Kickstarter. It's rather refreshing to see something like this, a return toward financial support for artists based on simple appreciation of their work. It's also interesting to note that it's a more populist system than in the old days. It used to be that artists had to seek out individual wealthy patrons. These new systems allow for funding to come from lots of individuals, so the artist is less bound by the whims of a few specific people.

Nevertheless, it's still an extremely difficult way to make a living. You have to be extremely lucky to end up as a rich artist. I think people underestimate the incredibly important role luck plays in that process if I'm honest. A great deal of western culture, particularly American culture, where I was born and raised, sells us the idea that success is a matter of pure effort and talent. But the American narrative conveniently leaves out luck.

Talent is great. Effort is important. Luck is essential. I've met countless talented people who receive little to no recognition for their abilities. I've met people who put in more effort than seems humanly possible but still don't seem to get anywhere. I've seen people who are both immensely talented and work extremely hard who continue to toil in obscurity.

I've never seen anyone be successful without a whopping dose of good luck. Not one. Not ever. Whether it's the luck of being born wealthy or being noticed by the right person or just happening to take hold of the right trend at the right time, luck is always a factor. (I've also seen successful people try to retroactively downplay the role of luck in their lives, attributing it all to talent and hard work, but that's a discussion for another time...suffice it to say that, because western culture teaches us that the route to success is hard work and talent, we tend to assume those things of anyone successful, including ourselves.)

So yes, I'd go so far as to say that, of the talent/effort/luck trifecta, luck is the only one that's an absolutely necessary component. I'm sure we can all think of someone who is successful to whom we don't attribute much in the way of talent, effort or both, but rather just seemed to luck into it.

I don't mean to denigrate those people, by the way. Luck isn't a cheat. Like I said, it's a necessary component. With all due respect to the old saying, I'd say it's more like "Success is 5% inspiration, 10% perspiration, 75% luck."

And most people aren't that lucky. Most people who choose an artistic career will likely not become rich or famous. They're doing it because they're so drawn to the art that they eschew a more lucrative career in favor of pursuing their artistic calling. In short, they're not in it for the money.

So the idea that the difference between "high" and "low" art rests in whether the motivation is artistic or financial kind of falls apart because...well, all artists do what they do for love of the art. They might dream of being rich and famous (as do many people in many walks of life) but no one really thinks being an artist is the quick path to that. It's all about love of the art.

So if the difference between "high" and "low" art isn't about the artists motivation, what is it about? What about the art's purpose then? What about what the art is trying to do? Perhaps art is "low" when it aims to do something less than savory?

That brings us to propaganda art, art that sells. Art gets used to sell many things, both products and ideas. Every time you see a commercial, it's a piece of art designed to get you to buy something. When you see a documentary, it's designed to sell you on an idea (documentaries, despite what some believe, are rarely neutral observation pieces.) Even general works of fiction are often selling an attitude or a worldview.

Is propaganda "low" art and "high" art that which doesn't try to influence the observer? That's a problematic position because, well, all art tries to influence the observer. People will sometimes claim that they prefer art which just raises questions, as opposed to influencing the observer toward specific answers but it's worth noting that even that kind of art is exerting influence to narrow the observer's attention to those questions themselves. People can watch A Few Good Men and come away with differing opinions on the value of following orders versus exercising personal responsibility but it's very hard to watch that film without contemplating the question at all.

Which begs the question, is propaganda bad? That's a very large question. I would go so far as to say that most propaganda has at the least the potential to be negative, if taken at face value, especially if care is taken to present the propaganda as if it's not propaganda but fact (something which some artists are particularly skilled at.) Indeed, that is the goal of the more insidious propaganda pieces, to get the observer to eschew questions and just jump on board with what the art is selling.

That said, what's being sold is arguably an important distinction between good and bad propaganda. A PSA about the importance of brushing your teeth is selling something considerably more benign than a pro-Fascist puff film like Triumph of the Will.

But, even then, "good" and "bad" aren't the same things as "high" and "low." The former is judgment about morality, the latter one about taste and class.

Can art promoting "bad" things still be "high" art? The Triumph of the Will has stunningly good camera work and editing despite it being propaganda for one of the most awful ideologies to ever exist. The 1915 silent film The Birth of a Nation is a nasty, racist propaganda piece that literally spawned a resurgence of the KKK. It's propaganda at its ugliest. It's also incredibly important in terms of the technical innovation of film. I'm glad I saw it once because of the latter but I can't image ever wanting to see it again because of the former and it still leaves a bad taste in my mouth when I think about it.

But the wider question there is, can technical artistry trump the "message" the propaganda is trying to sell? I'm not sure I have an answer to that question. I know there are stories I've experienced where I appreciate the way the story is told, despite not caring much for the story itself. (Pretty much every Woody Allen movie falls into that category for me.) But I also know there are stories I've found so reprehensible that no amount of technical skill can trump the fact that I think the message of the story itself is awful.

And what about when the artistry itself runs counter to the message? What about when the artist subtly fights against the propaganda they're tasked to sell? Or even not-so-subtly? Anyone who's seen a Paul Verhoeven film knows they're chock full of ultra-violent, right wing action. Anyone who's paid attention as they watch one of his films knows they're also filled with little jokes and asides that mock the very conservative message the characters and plot are selling...and it ain't subtle mockery. Is propaganda still propaganda when the artist deliberately undercuts the larger message of the piece? Or is that just propaganda of a different sort? Starship Troopers may mock the nobility of war but it's still a war movie. The same is true of Saving Private Ryan. Yet most people would consider those two films to fall on different sides of the "high"/"low" art divide.

At the end of the day, using a piece of art's status as propaganda or not as a measure of whether it's "high" or "low" art falls down because there really isn't any art without at least a small propaganda element to it. Art is borne of the world and those who live in it, carrying their worldviews from the artist to the observer, even if that was unintentional. Art's always selling something. Whether that something is a product or a large-scale political movement or just the invitation to think about things a bit differently, it's never neutral. It's always trying to have an effect.

So if "high" and "low" art can't be defined by whether or not they're trying to sell something, can they be defined by who they're trying to sell to? Different works of art are aimed at the different people, clearly. The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was clearly not painted with the same audience in mind as Calvin and Hobbes. It's not just that their intended effects are different but that they're designed for consumption by different sorts of people.

When one watches a film, one can usually get a sense of whether or not it was created with the intent of winning an Oscar or if it was aimed for more populist consumption, whether it's targeting the critics or the masses.

Is that the divide then? Is "high" art aimed at the critics who can appreciate its nuances and "low" art at the masses who can't? I suspect this is probably the closest I've come in this musing so far to how most people actually conceptualize that divide. This is usually what people mean when they separate a Vincent Van Gogh from a Jack Kirby into different categories.

But...I just don't buy it. No matter how common that viewpoint is, it's inherently flawed. It rests on the disturbing (but all too common) belief that there are people whose views matter and people whose views don't. There's an inherent elitism in the notion that the masses can't understand or appreciate art, that they are, effectively, stupid.

Now, I don't question that education and experience can increase one's ability to observe and articulate thoughts about the detail of art. But I do question the idea that the lack of those elements reduces someone's ability to examine art to that of unimportance. Even if someone hasn't yet figured out how to properly express how a work of "high" art speaks to them or moves them, it doesn't mean the art isn't having that effect. And just because a critic has decided to dismiss that same piece of "low" art as ineffectual doesn't mean they're right. The mere existence of critics and experts doesn't make everyone else an idiot.

Critics also bring their own biases to their observations, just like everyone else. Indeed, they're often more prone to bringing that specific "high"/"low" art bias to the table than others, dismissing something as unworthy of consideration out of hand because of many of the various reasons I went into earlier in this musing. I've lost count of the amount of people I've seen dismiss, say, the Marvel Cinematic Universe films out of hand with offhand comments that make it clear, not that they've observed those works and found them wanting, but rather that they've viewed only on a surface level and missed all the important parts of them. Heck, Martin Scorsese did it. If there's a better example of an expert bringing his own biases to the discussion of a work of art, I can't think of it. Scorsese is a brilliant filmmaker...whose comments on the MCU demonstrate that he judged based on a cursory glance, not a real examination, the kind of examination he's enjoyed for his own work for decades.

The modern era has also given rise to the emergence of the amateur critic. This is a good thing. The examination of art is no longer restricted to a professional elite. More voices and more eyes looking at works of art, picking them apart for meaning is great, especially if it expands outside the sphere of establishment criticism to allow for viewpoints that dissent from the conventional wisdom.

Unfortunately, what I frequently see these days, is amateur critics adopting that same elitist attitude that the professional ones often did. It's almost like the very act of choosing to do critique leads people to believe that they're smarter than everyone else, that their observations are universal and important, not just one voice amongst many. Heck, I'd be surprised if I don't come off like that sometimes.

At the end of the day, the elitism of critique boils down to this bizarre belief: "I can understand this piece of art. You can't."

But that misses the whole point of art. Art is understanding. Art is a way of looking at the world and making sense of it. And sharing that art with others is a way of sharing that understanding. They may not agree with it. They may not be able to articulate it. But that shared link of understanding is there. And you don't need to be a critic to be a part of that.

In a way, that whole critic/masses divide can be summed up in yet another possible (and frequently used) definition of the difference between "high" and "low" art: "Low" art appeals to the lowest common denominator.

I always think the emphasis in that statement is wrong. When people say it, they always stress the word "lowest" when it should actually be on "common." Because the lowest common denominator is also the most universal.

Surely a work of art that appeals to people on a more universal level is more powerful than one which speaks to only a select few. The idea that appealing to concerns of the masses is a bad thing seems like not just dividing art into "high" and "low" but dividing people along those same lines...elitism at its most distilled. How can a subject that affects millions of people be less important than one which affects just a rarified few? A work of art that speaks to how people are affected by love, sex, childrearing, paying the bills or gas prices touches on fundamental aspects of the existence of countless people, things that matter to them.

Mind you, I'm not saying niche subjects don't matter or are completely unimportant. If anything I'm saying that any subject matters as long as it's approached honestly and artistically. It's not the subject but rather what you do with it.

Because surely the value of art is in the effect it has on us as individuals, regardless of who we are and our place in life. And all art affects us, not just the heady "high" stuff.

I mentioned above that I consider jokes to be an art form. But if that's true, which are better, complex jokes or crude ones?

Who care as long as you laugh? A "classy" joke that isn't funny...still isn't funny.

Humor, both complex and crude, is also an excellent doorway into examining larger social issues. There's no better way of determining what the boiling points of a culture is than to look at its current humor...but that's a musing for another time.

The same is true of other forms of art. The power of art is in its ability to have an effect on those who experience it. Andrew Wyeth's painting, "Christina's World", is a painting I find very moving.

To me, this work speaks of loneliness, determination and the barrier of distance the world throws up against those who are different. To others I've spoken to (particularly those with disabilities), it speaks to different things. Their experiences and mine might overlap, but they won't be identical.

Who would I be to invalidate their experience? Who am I to presume myself smarter or better? What matter if the work affects us differently as long as it affects us? Surely any work that moves us is valid.

Why is it acceptable for adults to cry at opera but only for kids to cry when Mufasa dies in The Lion King? Well, I ball at that second one every time and I feel no shame about it.

I like a lot of what is generally considered "low" pop art but I enjoy "high" art as well. I'm also not blind to some of the parallels between some of them.

When I watch the first Doctor Who serial, I don't miss the character and plot parallels to Shakespeare's The Tempest. I haven't missed how similar the tropes of superhero fiction are to those of ancient god myths.

Sometimes "high" art is powerful, but sometimes "low" art is as well. I find Romeo and Juliet to be mildly sad but mostly a just cautionary tale. But I balled my eyes out when Optimus Prime died in Transformers: The Movie.

And that extends to every work. The power of art is to move us in our hearts, not just our minds and there's value in any art that does so, no matter how it came to be and who it's aimed at?

"High" art? "Low" art? As I said in the beginning of this musing, I don't buy into that divide. In examining the various ways to define the divide itself, I hope I've managed to articulate why.

Previous Post: The Menace of the Miracle Man

Previous Musing: Canon vs. Continuity vs. Lore

Next Post: The Dead Planet

Next Musing: The Flawed Hero and the Sympathetic Villain

First Post: Stories

Comentarios