The Elasticity of Continuity

- styrofoamturkey

- Feb 24, 2022

- 11 min read

Updated: Mar 13, 2024

or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love UNIT Dating

Not long ago, I talked about how I think continuity should be a toolbox, not a straightjacket.

That idea stemmed from the perspective of the creative side of things, from the desire to be able to stretch and twist and expand the story beyond its original parameters and how sometimes that requires changing things.

But what about the perspective of those of us experiencing the story, those of us who've been following it from the beginning and know the ins and outs of the backstory, the continuity? It's all well and good to say that creators should be able to alter things as they go to tell their story but those of us who've been there from the beginning know that Captain America wasn't a Hydra agent, Scully's kid wasn't created by the Smoking Man and the 1st Doctor was William Hartnell, darn it!

How do we cope with it when the new story alters something that we have always thought to be true of the old story?

We make a game of it, of course.

Most of us have been doing this for years, anyway, even if we're not conscious of it. We do it to explain away all the little niggles and inconsistencies in the narratives we like, the ones that were already present when we discovered it.

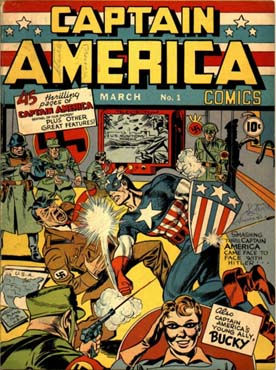

We know the Enterprise is a Starfleet ship, representing the United Federation of Planets, so we ignore it when Kirk says it's from the United Earth Space Probe Agency early on. We know the Doctor has two hearts, so we look at the ceiling as Ian only hears one heartbeat when he checks on the Doctor in The Edge of Destruction. We know Captain America's shield is made of an indestructible metal so we subtly let our eyes roll over the panel in Avengers # 6 when they impossibly open it up like a pocket watch to show all the cool things Tony Stark has installed inside it. We whistle loudly and don't question why James Bond and Blofeld don't recognize each other in On Her Majesty's Secret Service even though they met, face to face, in the previous film. (And no, it doesn't work to just assume OHMSS happened first.) For that matter, we whistle and ignore not just Bond's ever changing face but his ability to remain in his early-mid '30s from for about 40 years.

But it's not all just about deliberately ignoring things. Sometimes it's actually an exercise in imagination. How can we paper over this element which makes the story seem inconsistent so that it all feels like one, unbroken narrative again? We invent conventions about multi-Doctor stories and memory loss to explain away why the 2nd-5th Doctors don't all know, ahead of time, who the villain is in The Five Doctors. We add new first and middle names to Dr. Robert Bruce Banner to explain away why, for one issue, he was called "Bob" instead of "Bruce." We insert whole extra seasons to explain away the 2nd Doctor's memory of things that happened in the final moments of his last episode.

I say "we" but the truth is that this is largely an individual game. The goal is to reach a point where we're comfortable with the level of consistency in the fictional world, but each of us has a different threshold for such comfort. Some of us are looking for ironclad consistency, for the story to feel like a completely realistic chronicle of events, even if they are fanciful ones. Some of us have a looser approach, willing to let small inconsistencies slide but feeling a need to explain away the big ones. I really don't care that Kirk calls the Federation UESPA in the early episodes of Star Trek but it does bug me that Khan recognizes Chekov when they've never previously met. I just ignore the first one but posit an offscreen meeting for the second. We all have different thresholds for believability.

Still, sometimes these explanations gain traction among fandom and become the "standard" way to explain them, to the point where they eventually get adopted by the creators themselves. Bail Organa ordering C-3PO's memory wiped is the text of Star Wars confirming what SW fans had been assuming happened anyway. Season 6B is well-entrenched in Doctor Who's expanded universe (no matter how much I personally don't like it.)

None of this is a bad thing. The whole point of fiction is to fire the imagination. If fitting a few square pegs into round holes makes the experience better then that's a good thing, a constructive one. It's a fun one too. Trying to figure out how to make the story fit consistently is like trying to put a complicated puzzle together or trying to solve a locked room mystery. It's an exercise in stretching our viewpoint beyond simply soaking in a story and, instead, actively engaging with it.

You'll note that, while I've given some examples above, I haven't talked much about how I personally paper these inconsistencies over. That's because I feel that this is a very personal game. As I mentioned above, everyone has a different threshold for what kinds of inconsistencies bother them.

I, for instance, never felt like the difference between the way Klingons looked in the original Star Trek series and its later sequels needed an explanation at all. The makeup improved so I just took it as read that, as the series' progressed, we were seeing what they had "always" looked like but now the effects had progressed to make it more clear. Then they did that time travel episode in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and made a joke about the difference. I was fine with that. It was a single meta-joke, and a pretty funny one at that. Then they did a big three-part story in Star Trek: Enterprise which seemed to serve no purpose whatsoever but to explain away the change in makeup. I, honestly, thought that was one of the dumbest premises for a Trek story ever.

But it's there. The story isn't bound by my personal threshold for inconsistency any more than it is by anyone else's. Everyone gets to play the game, including the creators of the story themselves (although their choices do end up carrying more weight.)

No, other fans playing the game differently than I do doesn't bother me. Creators playing the game differently doesn't bother me either. (I might end up not liking that particular part of the story as much, but I'm always going to like some parts better than others anyway.)

What's more perplexing to me is when some people decide to stop playing the game entirely. I don't mean that they never played it in the first place, but rather that, at some point, they simply decide to stop, that the continuity of the story is now "set" and further alterations are no longer allowed, despite them having been permissible before. No longer are new additions to the continuity welcome, they are rejected simply because they are new. Spock having an adopted sister we never knew about is too much (even though we'd accepted him having a half-brother we didn't know about.) The Doctor having incarnations before the 1st that we didn't know about is too much (even though we'd accepted him having an extra one between his 8th and 9th selves.) Luke Skywalker giving up the fight against evil and going to live like a hermit is too much (even though we accepted it when both his mentors did exactly the same thing.)

In other words, at some point, we fasten the straps on the continuity straightjacket. No more changes allowed.

Some will say that personal politics plays a part in this decision. I'd be lying if I said I didn't think that was at least a small factor. I don't think it's a coincidence that the most vehement rejections of continuity change tend to coincide with attempts to expand the spotlight of popular culture beyond the focus on the straight, white male.

But I don't think that's all of it.

I've heard a notion put forth. I originally saw it attributed to Douglas Adams, late writer of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and former script editor for Doctor Who (though I honestly don't know if he's where it really came from.) The notion is that we learn about the world when we are a child and we accept that concept of the world as the correct one. Up until we are about 25-30, we remain willing to incorporate new information about the world and adjust our conception of it accordingly. But beyond that, certainly by about the age of 40 or so, we come to believe that we understand the world completely and new concepts, particularly ones that challenge our previous notions, are rejected. Basically we go from learning to understand how the world works to expanding our understanding of how the world works to thinking we already know everything there is to know about how the world works.

I have found this notion to be somewhat applicable to the exploration of fiction as well. When we first encounter a fictional universe that we are captivated by, we go through a period of trying to learn everything there is to learn about it. After a while, we start to have a sense of the fiction's history (which often already includes some contradictions) but we are still willing to have that history expanded and even contradicted for the sake of a good story. And then, at some point, we tend to view that history as set in stone and further expansions and alterations are no longer welcome. We cease to view a continuity change as an opportunity and start to view it as an assault on the thing we enjoy. We're not longer looking to explore this fictional universe, we're just looking to preserve it.

Now I've already talked, in my previous musing, about the dangers of approaching fiction with preservation of the status quo as the goal. So let's talk about the other side of it, the advantages of keeping your mind open to continuity changes as you go.

There's an intoxication to the initial exploration of a story. It's a bit like a budding romance, that time when you're first getting to know your potential partner and each new element you learn makes them more alluring. It's also the time when you tend to be most forgiving of the little things that are less than perfect about them. She has a beautiful smile so who cares if she snorts a bit when she laughs? He's so supportive and sensitive so does it matter that much if he forgets to do the dishes a couple times a week? Yeah, they've got a lot of cats and I'm a dog person but they're both furry pets, right?

The UNIT stories are fun so does it really matter if the dates for them don't line up perfectly? Five rounds rapid!

Like a relationship, it's healthy to move beyond that initial intoxication, into a more stable period, but one that continues to grow and evolve, if not at the same rate it did in the beginning. This is the period where you're sure you love the person and now you're just figuring out the ins and outs of things. You never realized she liked to play Dungeons & Dragons. Cool, you like D&D too. Oh, she always plays a bard? Well, bards get a little tedious, but it's still D&D and that's fun. You didn't know he could cook lasagna and you're fascinated to try it. Oh, it's vegetarian lasagna and you're very in touch with your inner carnivore? Well, it's just one meal. It's not like he's asking you to go vegan.

They did another UNIT story and it not only gets the dates wrong but it contradicts enough of the previous ones that reconciling them is impossible? Damn. Still...the Brigadier's back. Two of him, in fact. Cool.

And then sometimes, unfortunately, relationships become static. They just go through the same motions over and over again, never progressing. The goal becomes maintenance, not evolution. She cut her hair? But when I met her she had long hair and I liked that! He wants to go to dinner on Friday night this week? Doesn't he know that date night is Saturday night?!

They did a new UNIT story and some of the dates aren't right. That makes the story wrong, wrong, WRONG!

That last one is a fundamental shift, not in the way the continuity game is played, but in what game is being played at all. The original game amounts to "The story has some contradictions. Let's see if we can make it all fit." It's an inclusive, constructive game where the goal is to take all the disparate parts and make them fit together into a cohesive whole. It's taking a look at the Doctor growing an extra hand in The Christmas Invasion and realizing that process can be adapted to explain away Romana trying out extra bodies in Destiny of the Daleks. It's seeing the Fugitive Doctor in Fugitive of the Judoon and noting how that could help explain the long-debated extra faces in The Brain of Morbius. Granted, everybody's threshold for when they consider that goal to be completed is different but the goal itself is the same.

But the altered game doesn't have the same goal. It's not about trying to make the parts fit. It's about trying to exclude new parts at all because the assumption is that the previous parts already fit perfectly. That last bit is an illusion, of course. Perfect, pristine continuity is almost non-existent in most ongoing fictional universes. Even carefully constructed ones, like Babylon 5, have continuity errors that must be papered over. (How many castes do Minbari have? What dress was Delenn wearing when she went back in time? What does Anna Sheridan look like?)

The new game isn't inclusive or constructive. It's restrictive and defensive. It ignores that the "perfect" continuity it's trying to protect exists only because people played the previous game. The new game prompts its players to posit motives for creators that are not in evidence, including both a regard for consistency on the part of previous creators who didn't actually have such regard (like Terrance "Continuity is what we could remember on a good day" Dicks) and a bizarre maliciousness on the part of new creators, ascribing to them the desire to actively destroy what's come before (like Chris Chibnall's Timeless Child arc...the one that explains the faces from The Brain of Morbius and specifically includes a memory loss so that it won't invalidate the past stories.)

The players of this second game do not, of course, actually have any evidence to support these supposed motives on the parts of the creators. They're invented, whole cloth. More than that, I suspect they're a necessary outgrowth of that second game. Because those playing that game don't see it as a game. They see it as some sort of righteous crusade, the protection of the Holy Writ of Continuity against the heretics who want to change it.

And they ignore how often the continuity has changed before. Oh, they'll explain away the previous changes if you point them out, but they'll completely miss the hypocrisy of being willing to do that but unwilling to do so for new changes that come along. That's why there's the need to ascribe motives to the creators. They need a reason for the new changes to be different from the old changes, for them to be bad, whereas the old ones were good.

But the truth is that they aren't different. Deciding the Doctor's got countless lives is no more of a continuity change than deciding he had 13 which was no more of a continuity change than deciding he had more than 1 in the first place.

Because the issue isn't the continuity. Continuity is flexible. It can bend and shift and change and does those things on a regular basis. It could do that from the beginning and it can do so now. Continuity has elasticity and it has that naturally.

It's the people experiencing the continuity who need work to maintain their elasticity. It's us who need to remember the joys of the first game and recognize the limiting nature of the second.

We need to remember that the first game enhances our experience. It's the fun one, where we're playing with our friends and each of us is having a good time. It's that beautiful, budding romance with endless potential.

The second game just makes us angry. It turns us into the old man, yelling at the kids to stay off the lawn.

And no one is having a good time with that old man around. Not even the old man himself.

Previous Post: The Man in the Ant Hill

Previous Musing: Continuity Should Be a Toolbox, Not a Straightjacket

Next Post: The Forest of Fear

Next Musing: Canon vs. Continuity vs. Lore

First Post: Stories

Comments